This month, we spoke with Kyle Smitley, a leader who built her first startup while finishing law school, and for the past ten years has dedicated her career to education as the founder and executive director of Detroit Achievement Academy and Detroit Prep, free public charter schools that have garnered national attention for their holistic approach to student development.

The schools' commitment to closing opportunity gaps has shown up in different ways, like diverting school resources to supporting families with bills during the pandemic, investing in teachers' health and wellness, and open-sourcing their operations for others interested in starting schools.

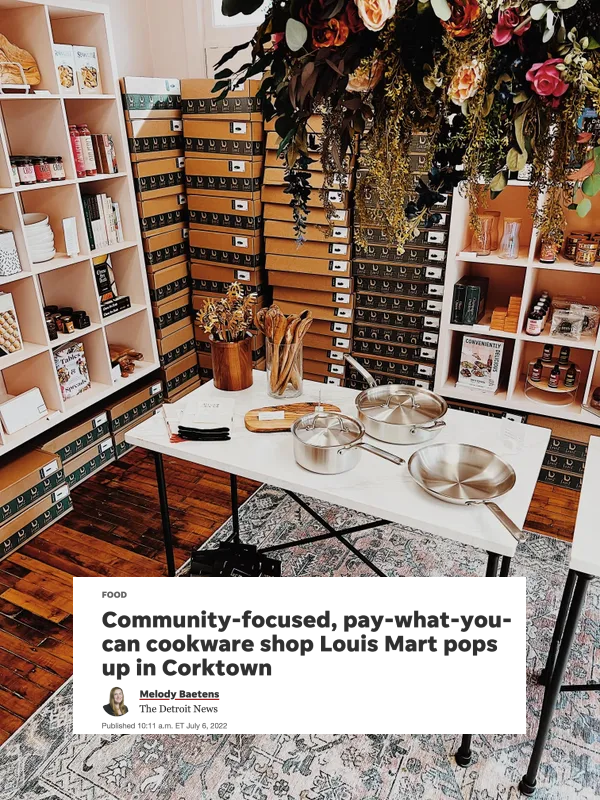

Not one to idle, Smitley has spent her downtime over the last three years building Louis Kitchenware, a community-driven, investor-free cookware company celebrating the everyday, home cook.

We sat down with Kyle to talk about her experience as both a startup and school founder, what the startup world can learn from educators, and her secret sauce to finding fulfilling work. Listen to the episode or check out some highlights below:

Can you tell us about yourself and all of the hats that you wear?

So I am the founder and executive director of Detroit Achievement Academy first. We opened in 2013. it is a small public charter elementary school that serves 300 students on the northwest side and we have alumni, we're in year 10.

I'm also the co-founder and executive director of Detroit Prep, which is a kindergarten through eighth grade elementary school on the east side of Detroit and we opened in 2016, so year seven there.

Then, three years ago, I founded Louis Kitchenware which is an amazing, exciting, kitchenware startup that is inspired by everyday home cooks and just wants to make everyone really excited to make dinner on a weeknight at home.

So, startup founder, decade-long leader. I'm also a parent and a partner to a frontline-hero emergency room doctor as well. So both of those can feel like a couple of full-time jobs too.

You built your first startup while you were finishing law school. Have you just always had this capacity to do a lot at once?

It was a perfect storm for me, stemming from a really small town. After I left that small town, it's sort of this voracious curiosity to do as much as possible and learn as much as possible and experience as much as possible. I like to work, I like to work hard. I like to meet people. I like to learn from people. I like to learn new things.

I always tell people, I feel like I'm playing house money. Every day is a privilege to be able to exist. It's a privilege that we're alive. It's a privilege that I have a roof over my head. It's a privilege I have some food to eat.

All of this is a privilege and so if I can max out other parts of my life, especially with an eye on service, that's, for me, the secret. If I had a normal day job or something, I don't know that I would be as hungry, but my secret sauce is being an impact.

So, coming from your startup background and deciding to build a school, what were the problems to solve and opportunities to address, in 2013 Kyle Smitley's mind?

In my mind, there were great schools in neighborhoods that had a high poverty marker in countless other cities in the United States. Why in Detroit, did that not exist? It was simple, right? It was like a recipe. If this can happen elsewhere, why in Detroit are we still letting adults blame kids and blame poverty and blame families for schools' failures?

So the problem I was trying to solve was can I–with my own two hands and on my back– can I raise a mountain from the earth?

Can I make an entire institution exist in a way that I feel pretty confident that it can, but that every human being in the entire state of Michigan has told me that it can't. Do I believe in myself enough to do it?

And my answer was yes.

Your schools have gotten national attention. You've been featured on the Today Show, Ellen and PBS. I know you're not one to rest on your laurels, so what are you excited to explore next with Detroit Achievement and Detroit Prep?

Our five year plan was what I did with a lot of our pandemic nervous energy; get feedback, iterate. We got feedback on how we did in our previous five year plan. We had town halls. It was all stakeholder-created which then translated into this super-aggressive five year plan around recruiting and retaining world class educators.

We get to be really picky with who we hire each year which is really cool, because we just have a limited number of spots open because we grow very slowly. So it's like, how do we keep getting the best people?

There's also a five year plan again around knowledge and skills, grade level content. We are outpacing neighboring schools and peer schools but there's still work to be done in closing every possible perceivable gap between our kids who live on the northwest side of Detroit, or on the east side side of Detroit, and kids in affluent areas where their schools are funded higher and their home lives might look different and the all facets of their life, and generationally, look different.

I just...I'm hungry to close that. I think we can do it.

What is going through your mind when that entrepreneurial bug starts biting again? How did Louis Kitchenware come about?

It was not a coincidence, it was a time in my life where I had enough disposable income to graduate past my law school hand-me-down cookware that my mom gave me. Okay, so what is pop culture telling me I should do with my disposable income? And the internet had nothing for me.

The internet had the major, big, stuffy cookware companies, ugh. I do feel included by that but I don't feel excited by it. I feel kind of excluded, kind of included, but I don't wanna be included, the type of marketing they do and how they talk and what sort of cooking they prioritize. It just felt, yuck.

Eventually, I said I wanna do it, and talk to other people. A lot of mansplaining, a lot of fund-splaining. A lot of, "I have a buddy who tried this, you should talk to him." "We looked at this, this, this, you know, the cost of goods, shipping big pieces of metal, it just doesn't work." You're gonna be importing it and you're gonna be doing this and this and this, and the numbers just didn't work. And I was like, okay, sure...

At the time, I was 7 months pregnant, so what am I gonna do? But for me, it was just the idea that wouldn't get out of my brain, so over the pandemic, I used all my nervous school shutdown energy to obsess over every detail, and by end of 2020, I realized I had a fully put together brand and supply chain and I had a supplier being like okay, sign here! And I was like, wait...how did I get here?

Do I still believe in this needing to exist? Yes. I still believe that this community needs to happen and this messaging needs to happen. And this concept of no, you're doing a great job. You're cooking at home, you're doing great. That needed to happen.

Part of Louis' messaging is that it's community-driven and investor-free. Why did you feel it was important to call that out and how do you execute on it?

In every corner of Instagram, it's telling me to go look at a cute brand. And I do, because I'm a millennial. Then I'm left on this brand's site, wondering is this a real thing? Is a real human being behind this? Or is this just some brand's, or fund's, exercise to see if it can trick millennials into spending money and doing a thing.

Whenever I have that internal cringe, I'm like, okay, great. I need to pay attention to that. And so we don't pay for ads, and that's on purpose. We want to use word of mouth, we want to use real things that are of interest to people to get attention and spread the word.

We aren't taking on investment dollars because I want to be able to be genuinely honest with people. I want to look at people and say, no, no, no, if you have a knife that you got six months ago, don't buy this knife, buy this other knife.

I want to be able to say that to someone and not have to look at someone and say, "all the other things you own are bad. You have to replace it with all Louis," because I have some investor-daddy on me, telling me I'm a failure because I'm not scaling fast enough.

I would rather grow only based on what our community needs and wants, and not what some schmuck in a Patagonia vest tells me.

Do you ever feel yourself veering towards burnout? If so, how do you walk yourself back from that edge?

Burnout for me, you don't say "I'm burnt out." You say "I hate you. I hate you, I hate you. I hate this, I hate this, I hate this, I hate this." One thing I never do is I never gaslight myself. For example, there is a lot that I need to get done in both this job and Louis.

Typically, if I'm healed and healthy, I have a lot of fire in my belly after my kids go to bed. So from 4:00 PM to 8:00 PM is protected time. My computer is closed, I have my kids, I have no email on my work phone. Maybe I'm texting some friends but for the most part it's kids and family–joy, joy, joy. That mostly refills my bucket. Kids are also kind of a whole situation, get ready. Sometimes it's draining too. I really love my kids and being around them so it refills me more than the average parent, I think.

Usually, I put my work bag right next to my bed because as soon as they go to bed, I'm excited to dive into a lot of the personal stuff like ordering my kids new socks and doing some really fun Louis stuff and finalizing this project and emailing this person back and doing this thing.

Three nights this week, I put my computer next to my bed to get in bed and do some work. And then at 8:00 PM I was like, don't look at me, to my work bag. Leave me alone. I don't wanna talk to you ever again.

I let myself off the hook all the time. I don't gaslight my decision making ever. And I never beat myself up about stuff. Those are my rules for burnout because what a waste of time. We can negative self-talk enough. Don't do that about your decisions about working. You can learn more about Kyle's work at the links below:

https://www.detroitachievement.org/

https://www.louiskitchenware.com/

Or follow along @kylesmitley on Instagram.